I reckon many of us have been debating this. Is this or isn't it what we used to call an "Indian Summer"?

The UK Meteorological Office has slapped our wrists several times in recent days.

We can't call this an Indian Summer they say.

Indian Summers can't happen in September, we learned to our surprise. They have to occur after the first frosts near the end of October or early November.

This, in spite of having spent our lives in blissful ignorance of the fact we needed permission to celebrate an autumn warm spell in whatever way we chose, under whatever name, whenever we noticed it. After all, surely it's the public's own words and traditions that put any concept into the culture in the first place? This delightful phenomenon was called an Indian Summer long before the Met Office, or the Governments who fund it, had us in a headlock over semantics!

The Guardian's Polly Curtis in the article linked above, quotes one of the earliest uses of the term, from Frenchman John de Crevecoeur, in 1778:

'Sometimes the rain is followed by an interval of calm and warmth which is called the Indian Summer; its characteristics are a tranquil atmosphere and general smokiness. Up to this epoch the approaches of winter are doubtful; it arrives about the middle of November, although snows and brief freezes often occur long before that date.'

It's been suggested the phrase is rather a disparaging reference to Native Americans perpetrated by the incoming European settlers, who branded the native dwellers as untrustworthy for breaking "treaties" with the invaders of their territories. Hence the unseasonal warm spell was deemed to be similarly breaking the settled pattern of the weather getting colder as the winter solstice approached.

I, for one, wouldn't be comfortable to use any term, whether deemed "non-PC" or not that could cause offence to those with a reason to feel aggrieved by certain loaded phrases. But it seems far from clear that this is the origin of the name for this meteorological phenomenon. The jury seems to be out. Or not to have realised they had been convened.

Wikipedia confidently states here:

Depending on latitude and elevation, the phenomenon can occur in the Northern Hemisphere between late September and mid November.

In many ways, the Wiki is the modern voice of popular cultural understanding, for all its limitations. So late September doesn't seem disqualified here! Wherever the Met Office has arbitrarily decided to draw a line in the sand.

|

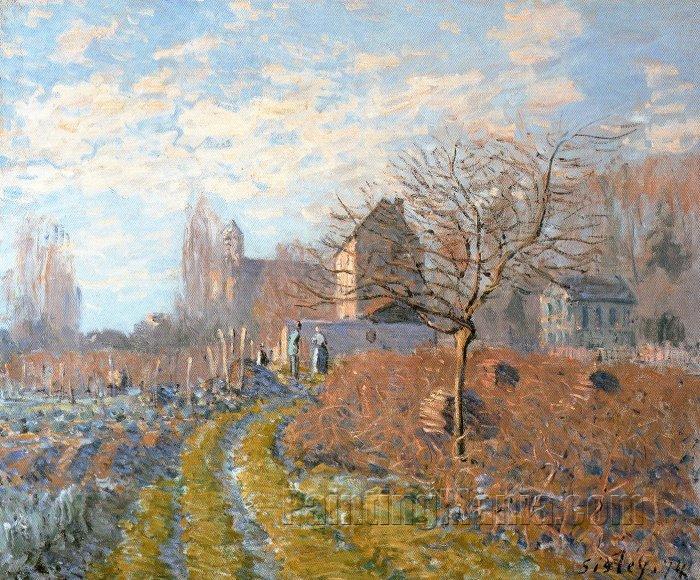

| Hoar Frost - St. Martin's Summer (Indian Summer) by British painter Alfred Sisley 1874 (Oil on Canvas. Private Collection) |

Looking at the numerous different names for the phenomenon from round the globe shows there's a huge collection of terms we can choose from. Some maybe less than flattering, many just sublime:

Little Summer of the Quince, Old Ladies' Summer, Summer of Old Ladies, Crone's Summer (non-PC for self-respecting modern women!), Gypsy Summer, Gypsy Christmas, St Theresa's Summer, All Hallown Summer, Return of Summer, Flashback of Summer, or the Chinese phrase meaning "a tiger in autumn", humankind has always wanted to speak about it and celebrate it!

Whatever it should be called, it's a joy when it happens, in my book. Because it's here, it's hot, it's glorious! Beautiful soft, golden days, melting frigid dawns and evenings after the tilt of the autumnal equinox. Lighting up the dying leaves and showing off their twilight splendour. Giving us hope that it's not so very long, after all, till spring.

No comments:

Post a Comment